My fellow black Americans, I shouldn’t be writing this, but I will continue on, nonetheless.

Several years ago, I joined a humanitarian aid programme in Congo thinking that it would be a one-way ticket through heaven’s pearly gates. Though as time went by, I realised that we were only helping these people to survive and not actually live and that’s not even the worst of it. Corruption. Sexual exploitation. It was colonisation masquerading as humanitarianism.

During my stay I became acquainted with a young Congolese woman named Jaëlle who did not like the camp either and she told me of her plans to flee to a secret society called Zama. What she described sounded like a fever dream. How could a society of all black people be more advanced than America? An African American one, perhaps, but surely not an African one. But I hoped that I was wrong and that there was black greatness out there in the world. She convinced me to join her and on a cool night we fled for Zama.

The Arrival

I cannot tell you how we got there; how long it took; or the sights we saw along our journey— that would be breaking one of the most important promises that we made when the Council agreed to offer us asylum. However, I can tell you that our arrival was no parade.

Jaëlle and I were greeted by thousands of red dots that outlined our bodies under the night sky like a child’s dot to dot drawing. Of course, my hands automatically went up in surrender, but Jaëlle made a shriek so fierce that I thought she was possessed by a demon. I hushed her with the hand closest to her face. ‘Put your hands up so they don’t shoot!’ This was not my first rodeo. Back home, I had been stopped and searched by the police for just being in the wrong neighbourhood. What didn’t she get? The hands behind those guns did not care if we begged for mercy— they wanted to see that we were not a threat. But Jaëlle continued pleading whilst I stood there numb, ready for the light at the end of the tunnel to soon appear. Her pleas became bestial and the intensity of the red dots increased. All I could see was red. ‘This is it— we are in hell.’ Suddenly she shifted and turned her body to me. She smiled as though we had been released from prison after serving a life sentence. As far as I was aware, the only crime we had committed was being born black in a white world.

One by one, I watched the dots fade from her dark skin. A gentle hand placed itself on my back and pushed me towards the light ahead. I could no longer see Jaëlle, but I sensed her smile and that brought me some comfort.

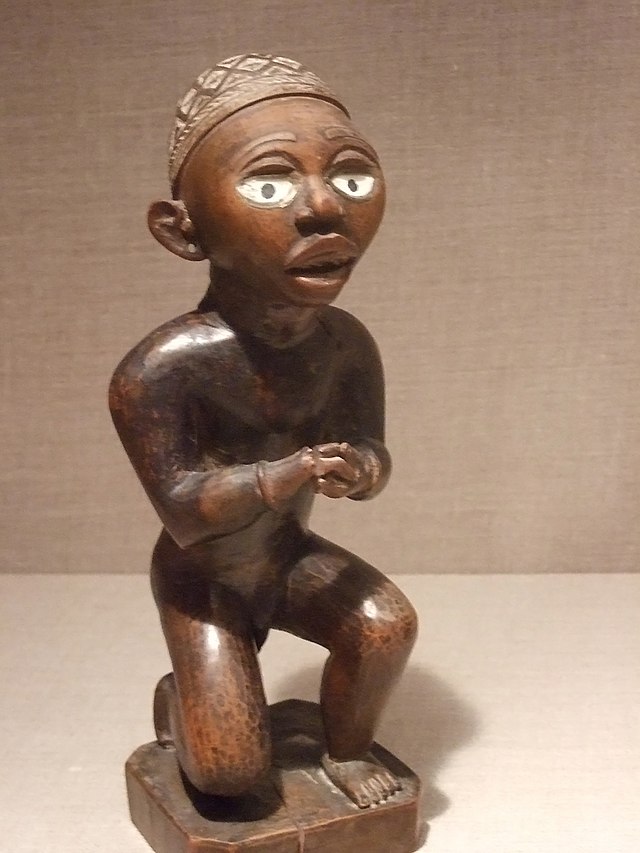

We were brought inside what can only be described as a concrete palace. It was truly a work of art. I remember thinking to myself ‘they must have built this before the slaves…’ But before I could finish my thought, the hand returned to my lower back and guided me inside a tiny room with a glass wall. On the other side of the glass stood people as black as charcoal like Jaëlle. Their features were round, and their hair was wild and overgrown. They were all truly black and compared to them I did not feel black at all. They looked like savages.

‘Who are you people? What’s happening?’ Where are we? Why have you put us in here?’ I blurted, unsure which question I wanted an answer to first. Their eyes widened like beasts ready to charge and I quickly backed into the corner. The two tallest men rushed in. One pinned me down whilst the other struggled to rip off my shirt. His hands were violently shaking as though he was nervous, but a tap on the glass encouraged him to continue. He pulled out a wire brush and began to attack my skin. Jaëlle attempted to remove him from my body but he pushed her tiny frame to the floor. He continued to graze at my chest until I started to bleed and then he suddenly stopped. His companion let me go and they headed towards the door with their heads down. These people were truly barbaric.

Before Jaëlle could rush to my side, a medic was sent in. Jaëlle tried to speak with him in a tongue I could not understand, which put me on edge because I was so used to her speaking with me in English only. I could not tell if she was selling me out or trying to defend me. How could I trust her if I did not understand her?

The man applied some sort of herbal ointment to my chest that burned like hell fire. I felt like a pig being prepared for slaughter. ‘Get off me you cannibal!’ I cried. Jaëlle smiled to reassure me that everything was fine, but it wasn’t.

From then on, I even watched Jaëlle closely.

The Council

The following morning two female guards escorted us through the city. To my surprise, the streets were paved and clean— something I hadn’t noticed amidst the panic last night. The architecture was opulent and rather elaborate and if it weren’t for their modest size, many of these buildings would put our landmarks to shame.

We arrived at a tiny building where the most beautiful woman in all of Zama stood at its entrance. Unlike everyone else, her skin was white. She was an albino with distinctively black features: a haunting beauty, indeed. Though I did not understand her greeting, her smile assured me that we were safe, and I allowed her to lead us to a room with a circular table at its epicentre. Ten men and women of varying ages were positioned around the table like the numbers on an analogue clock. I filled in the empty position of eleven, and the beautiful woman sat at six directly opposite Jaëlle at twelve. She began conversing with Jaëlle in a foreign tongue and Jaëlle responded accordingly. There were no words that sounded like English, so it felt like watching a foreign film with no subtitles.

Their exchange appeared to end amicably and Jaëlle turned to me and began speaking. ’They said that they apologise for the attack last night, but they had to be sure you were not a white man in disguise.’

‘Why on earth would they think that?’ I interrupted.

Jaëlle turned to the woman for an answer, but a rather stocky man sitting at four o’clock responded instead. ‘When the guards heard you speak in English, they assumed that you had been sent by the white men to finally complete their mission of colonising the world. You see, many centuries ago, Zama was an impoverished nation. Disease, starvation, misery and death.’ His spit cut through the thick air as he spoke. ‘But one family was particularly wealthy because the father was an intelligent man and a skilled hunter. His name was Mwikiza and his children were stronger and healthier than most. Though this brought him joy, Mwikiza could not stand to see his neighbours suffer so he formed a brotherhood and shared his knowledge with the rest of the community.’ It was then that I registered that the man spoke English, but I did not dare to interrupt his sermon. ‘All the children began to grow much faster and stronger and the people were so grateful for Mwikiza’s wisdom that they elected him to reform the country. We began trading with neighbouring villages who were less prosperous. However, there were no regulations to abide by and many men started to charge outsiders extortionate prices because people were so desperate to eat. Those who lived on more fertile soil even began exploiting their own neighbours, with one man being forced to sell his house to his kinsman to feed his family in the middle of a drought. Mwikiza was disgusted that greed had corrupted the hearts of his people. He pleaded with those who had exploited neighbouring villages to reimburse those they had taken advantage of. Some refused. But many adhered and asked for repentance. Though when they returned, their bags were still full. They informed Mwikiza that three of the neighbouring villages had been taken over by men as pale as the moon. The people of Zama were horrified, but Mwikiza ensured them that they would not be captured by these men. He raised an army and when the white men came, they did not expect to find the people of Zama strong and armed. The fight was over quickly, and the white men’s heads were put on spikes as a warning to anyone who dared to cross our borders again. We did not expect that the enslaved would escape and one day return home, so I can only apologise on behalf of the guards who attacked you last night.’

I was overwhelmed. How had they remained hidden all this time? I had many questions I wanted to ask, but I had to gain their trust first. ‘I assure you that I am black like you’ I began, ‘I merely seek refuge for I am an orphan of the past and wish to find a true home amongst your people.’

The council agreed that Jaëlle and I would undergo what they called an Immersion Period during which we would learn about Zama’s culture, the language (which Jaëlle appeared to be fairly fluent in already) and its history. We were assigned tutors each and had to complete ten hours of labour a week alongside our education. They asked us if we thought these conditions were fair and Jaëlle immediately said yes, but of course she did. All she knew was poverty and anything sounded better to her than the camp. She had no knowledge of law or citizenship. I, however, was sceptical. The proposal sounded rational enough, but where were the contracts? There was always a fine print somewhere and I wasn’t just going to sell my soul like that. ‘Lord knows what voodoo they’ll practice on me’ I thought.

‘We do not believe in contracts, but we are willing to cooperate with you. Tell us what you believe are fair conditions.’

This was the first time in my life that I had been asked what I wanted, and I had nothing. I had no other choice but to agree to their proposal.

The Language

To my delight, my tutor was the beautiful albino woman. Her name was Djoëlle and thankfully she spoke English too. I asked her how she knew the language and she told me that the leader of the white men’s army was held captive in Zama for nearly a decade.

‘He quickly took a liking to one of the female guards and began to speak with her whenever she brought him his food. She slowly learned English and fed back any information that would help the country protect itself. He fell for her and killed himself when he learned that she was pregnant by another.’

‘How cruel’ I muttered under my breath.

‘Many believe that she never loved him, but I disagree’ she contested. ‘Mwikiza and his council instructed her to make a record of what she had learnt so that if the white men ever attacked again, we would fight with our words rather than our weapons. I never imagined that the first native English speaker who crossed our borders since The Invasion would look like us. How did you escape?’

‘I was not a slave.’

‘So why did you leave?’

‘I wanted to explore the world.’ I choked. What was I supposed to say? We are no longer enslaved, but our people get killed every other week by the police. Or maybe, no matter what I do, I can never escape the burdens of being black. I wanted her to see me as a man. I did not need a pity party, so I swiftly changed the topic. ‘Does everyone here speak English?’

‘Only those who wish to. But the majority of the country speaks only Zamais.’

Zamais is quite simple really: there are no gendered pronouns, or feminine or masculine words; there are no possessive pronouns; intonation does not alter meaning and is instead used to indicate tense; there is no distinction between formal and informal, with the people using the same talk regardless of the context; there are also few adjectives and phrases to describe negative emotions. This will all hopefully make sense when I discuss the nature of the people. Oh, and there’s no way to express sarcasm… I guess that’s all the basics.

The Nature of the People

Despite the rough nature of the guards, everyone else appeared to be quite docile and sweet-tempered. People moved and spoke in slow motion. Even our tutors took their time with us, never rushing us and always encouraging further discussion. It was as though they had all the time in the world. I wondered how such calm people fought off the great white empires of the past. They had no tribal paint or pointy sticks and they certainly did not look like the mighty African warriors I had expected. The only thing threatening about them was the colour of their skin.

Of course, Djoëlle had an answer for everything: ‘Though the people had been victorious in battle, their spirits did not reflect this. They did not feast or celebrate. They mourned. They had lost more men and women in one night than they had in nearly twenty years since The Reformation. We are not violent by nature and our people only fight when it is necessary. Even today, conflict amongst our people is rare. If a dispute does occur, the two parties will set aside their differences for the good of the community. We think as a collective mind and always find the most peaceful way of doing things to avoid causing communal distress. Even when the white leader was captured, Mwikiza did not want to put anyone through the trauma of having to kill or harm another human again, so imprisoning him was the only ethical thing that the Council could agree upon.’

‘But the guards who attacked me…’

‘I said violence is rare but not extinct’ she interrupted. ‘An outsider who speaks English arrives on our soil for the first time in centuries… Now, you can see how that would be alarming, no? When they attacked you, they did it to protect all of us. That is the only time violence is permitted: to protect.’

‘They couldn’t have just questioned me?’

‘A man’s word is only valuable to those who know the man to be honest. Our people have built deep connections with one another and can feel each other’s pain. We do not lie because we can feel the truth between us already. Once you have spent time with us, your senses will have adjusted, and you will feel this pain too. But until such time comes, we cannot rely on your word alone because we cannot feel what’s in your heart.’

I remained silent. This sounded like a load of crap.

‘Trust me, my friend. The guards who attacked you felt your pain. They have taken a pilgrimage to cleanse their spirits for there is little glory in violence.’

Gender, Love and God

Once my Zamais had improved, Djoëlle took me on a trip to her family home. I was disappointed when I saw that her mother and sister were both dark.

I asked her sister if their father was out working to provide for them, but this confused her. ‘Is it not a man’s job to provide and protect… especially out here, you know?’

‘Sex only governs the roles in reproduction. Outside of this act, people behave however their spirit dictates. We do not define ourselves by gender, as your people call it.’ Her mother chimed in.

‘So, homosexuality is not a sin?’ I retorted.

‘I have studied the white man’s accounts of your religion and sin is the one thing I do not understand… What is abhorred to one person, is often natural to another. So, should we not allow each other to live freely? If we were to impose our beliefs onto one another, this would cause a deep universal suffering that would surely lead to our destruction.’

‘But the fear of sinning prevents murder and other heinous crimes. That way everyone makes it to heaven.’

‘Murder of a petty, selfish kind rarely takes place here. As I said, our empathy keeps us aligned. And as far as we’re concerned this land is as good as any heaven we are going to get. There is no need to threat about life after death when there is so much joy now’ Djoëlle interjected.

‘So, I’m guessing if you have no contracts and you do not believe in sin, there is no marriage either?’

‘People do not belong to people, just as land and trivial possessions do not belong to people. Of course, there are those with closer bonds than others, but we all belong to Zama and, in a sense, that is our only form of marriage’

Insemination

Jaëlle and I have been fully immersed into Zamanian culture for five years now and I have to confess that the only think keeping me here is Djoëlle. I have tried to be kind about these people, but I must tell you how I really feel now.

Back home, I might’ve been seen as nothing but black, but at least I was still a man. Here, I cannot impress Djoëlle by promising to hunt and provide for her because gender is not important. What is more shocking than anything is that not only does Djoëlle not see herself as different to the others, but the others don’t treat her differently either. Perhaps, that is why she was so surprised when I expressed such strong interest in her. And why wouldn’t I? She is a beautiful albino fairy but courting her is dull. There is no chase. No excitement. No fight. I expected to be competing against savages to claim the prettiest girl and instead I have joined the most pathetic, emotional society known to man. Before I arrived here, I had thought the modern black man had become too effeminate and weak. Boy was I wrong. This is degeneration not evolution, my friends. You would not believe that these are the people the white men once called bestial. The black men here are whiter than white.

This so-called ‘peace’ cannot continue. Mwikiza may have been wise but he was clearly too weak to lead these people to glory. Even the guards who attacked me are not real men. Real men do not take a pilgrimage to cleanse their spirits. Real men return to their wives after battle to be worshiped like kings.

All hope is not lost, though. Tomorrow I will meet with the council to see if I can make reformations. I want to show the world that black people do live in glory, but these people are too pathetic to showcase to the world. Plus, we need to be strong enough to defend ourselves if attacked and empathy is not going to save us. If the meeting doesn’t go well, I pray that the son Djoëlle and I produce lives up to my family name and sees the truth about this country. But until such time, I cannot disclose the exact location of this society.

Pray for me my men for this task will not be easy.

Commentary

As Zamalin points out (2019: 7) ‘black American life [and arguably black life globally] has been nothing short of dystopian.’ While black people’s position in modern society has improved, the colonial past continues to haunt the black subject. In this commentary, I will discuss how this utopian vision has destabilised the black subject from dystopian themes of brutality and destitution, creating an image of black excellence that explores what black society would look like if it had evaded colonisation.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s novel Herland (1915), which depicts an all-female society, served as the primary basis for the key element of a homogeneous population. Gilman’s decision to strip Herland’s women of their femininity is arguably the most noteworthy element of her feminist utopia because it allows Gilman to undermine the biological determinism that has been used to justify patriarchal mandates that normalise sexism. In order to undermine similar negative notions about black people, I have depicted the people of Zama as hyper-black, if you will (or at least in regard to physical appearance): ‘people as black as charcoal… they were all truly black— and compared to them I did not feel black at all’ (2). Despite being indisputably black, the narrator suggests that the people’s docile nature is almost oxymoronic to their dark complexions: ‘pathetic, emotional… too effeminate. This is degeneration…The black men are whiter than the white man.’ This juxtaposition has been employed to disassociate blackness from stereotypical notions of ‘barbarism, savagery, heathenism, and ugliness’ (Hunter 1998: 3). Moreover, this challenges the notion that the rational subject is always one who is male, western, and white, highlighting that these characteristics should not be used as a yardstick to measure humanness (Greenblatt 2016). There is also a sharp contrast constructed between the lightness of the protagonist’s skin and the dark skin tones of the Zamanians. This compulsive focus on skin tone serves to illustrate how colourism, i.e. ‘a subversive form of racial oppression hidden within the machinations of racial discrimination that awards advantages to black Americans based on the lightness of their skin’ (Dowie-Chin et al. 2020: 135), influences mate selection and the general treatment of others amongst black Americans. For instance, parallel to the three male protagonists’ selection of Herland’s most feminine women, the male protagonist determines that Djoëlle is ‘the most beautiful woman in all of Zama’ (2) because of her albinism. While this addresses the intersection of race and femininity that Herland overlooks, one can argue that, like Herland, this utopia has further limited representations of black people by suggesting that there is only right way to be black. Bowers (2018: 1319) suggests that Gilman’s focus on how Herland’s women differ from men ‘conforms to the essentialist view that women’s identities are defined by their biological differences from men’— or even other women, for that matter. With this in mind, the same may also be said for my utopian vision. However, the fact that Djoëlle claims that ‘once you have spent time with us, your senses will have adjusted’ (5) indicates that the difference constructed between the people of Zama and those of the Western world is due to socialisation and not biology. This demonstrates that, unlike Herland, this utopian vision does not ‘conform to the essentialist view that [black people’s] identities are defined by their biological differences from [white people]’ or African Americans (Bowers 2018: 1319).

Levitas (2000: 30) notes a rise in anti-utopianism (i.e. ‘the denial of the merits of imagining alternative ways of living, particularly if they constitute serious attempts to argue that the world might or should be otherwise’) in the latter half of the twentieth century and Zamalin (2019) discusses similar instances in black anti-utopianism from Richard Wright’s Black Power (1954) to Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993). Nonetheless. it is important to note that both Levitas and Zamalin argue that the definitions of utopia and dystopia are ambiguous. Zamalin (2019: 8) highlights that despite being a post-apocalyptic novel, Parable of the Sower ‘offers a utopic image based on a community of hope and resilience’. The foundation of this utopic image is Butler’s notion of hyper-empathy, which she suggests could dispel many of the brutalities that have become commonplace in her imagined 2020s society: ‘But if everyone could feel everyone else’s pain, who would torture? Who would cause anyone unnecessary pain?’ (102). While this idea was merely a utopian hypothesis in Butler’s novel, I have brought this idea into fruition, using it as the second key element of my utopian vision. Dissimilar to Herland in which motherhood and parthenogenesis ensures that the country remains self-sufficient and sustainable, it is hyper-empathy that stabilises Zama and ensures that the people do not succumb to greed or other destructive ideations. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the hyper-empathy evident in this utopic vision is not identical to Butler’s: the key to empathy is knowing a person’s character, which is achieved through communication rather than merely seeing someone’s pain. Yet the Zamanians initially react to the protagonists with violence and do not adhere to their established social mores. This contradiction serves to establish that Zama is, perhaps, not as peaceful as it presents itself to be. Despite Zama’s advancements, the threat of colonisation appears to trigger an ancestral rage that induces violence: ‘their eyes widened like beasts ready to charge’ (3). This confirms Butler’s insulation that empathy, in fact, makes humans even more self-serving and is simply a utopian paradox. Moreover, even though the protagonist has been fully immersed into Zamanian society, he exhibits no signs of empathy and maintains his initial disdain for their customs, highlighting that empathy is futile and only effective amongst Zamanians. This utopian contradiction showcases that utopic ideals of eternal peace are flawed, especially in relation to the context of racial divisions. It is clear that this utopic vision is closer to Butler’s rationalised vision of Western society and that, unlike Gilman who merely attempts to ‘provide a sanctuary for readers to visit in order to gain a vantage point outside the prevailing culture’ (Peyser 1992: 1), I have provided a vision that is hopeful, yet still acknowledges the very harsh realities of the world in which we live.

In conclusion, I have managed to destabilise the black subject from dystopian and colonial themes, focusing on how the black subject could achieve glory in an all-black society, whilst also discussing how such visions would be difficult to sustain given the fact that we do not live in a post-racial world.

References

Bowers, E. (2018) An Exploration of Femininity, Masculinity, and Racial Prejudices in Herland. [online] available from <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ajes.12253> [5 April 2020]

Butler, O. E. (2019) Parable of the Sower. New York: Grand Central Publishing

Dowie-Chin, T., Cowley, S. P. M. and Worlds, M. (2020) Whitewashing Through Film: How Educators Can Use Critical Race Media Literacy to Analyze Hollywood’s Adaptation of Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give. [online] available from <https://ijme-journal.org/ijme/index.php/ijme/article/view/2457> [5 April 2021]

Gilman, C. P. (1978) Herland. New York: Dover Publications

Greenblatt, J. (2016) “More Human Than Human”: “Flattening of Affect,” Synthetic Humans, and the Social Construction of Maleness. [online] available from <https://muse.jhu.edu/article/648687/summary> [5 April 2021]

Hunter, M. L. (1998) Colorstruck: Skin Color Stratification in the Lives of African American Women. [online] available from <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1998.tb00483.x> [5 April 2021]

Levitas, R. (2000) For Utopia: The (Limits of the) Utopian function in Late Capitalist Society. [online] available from <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13698230008403311?journalCode=fcri20> [5 April 2021]

Peyser, T. G. (1992) Reproducing Utopia: Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Herland. [online] available from <https://www.proquest.com/docview/1297874428?accountid=10286&imgSeq=1> [5 April 2021]

Wright, R. (2008) Black Power. New York: Harper Collins Publications

Zamalin, A. (2019) Black Utopia: The History of an Idea from Black Nationalism to Afrofuturism. [online] available from <https://www.jstor.org> [5 April 2021]